BLOG POSTS WHERE MONTH IS 11, AND DAY IS 11, AND YEAR IS 2015

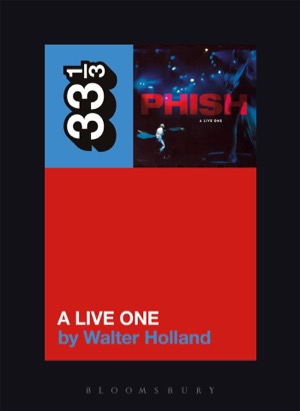

"A LIVE ONE" THE BOOK

“...I just had a long phone conversation with Trey. ... he'd like to ask the net to do him a favor...

So, the favor is this: if you have the time to do it, please consider constructing the Phish double live CD that you would like to hear. Please bear in mind that this CD should be interesting to people who have never heard Phish before, as well as those who have been listening to them for years. Please remember to consider that versions of songs from lesser-known shows may be as good as, or better than, versions of the same songs from well-known shows such as Halloween and NYE.

The format is two 70-minute CDs ("CD1" and "CD2"). Consider the transitions between songs, and the pace and dramatic flow of the order in which the songs occur on each CD. ... We're not saying that the net's compilation will become the live CD, by any means; but the band will listen to it with open ears, and if they like it, they will seriously consider the suggestions it makes. –Shelly”

(FULL DISCLOSURE: I have been reading Wally’s musings on Phish and music and other topics since the 1990s, and to this day I’m still in disbelief that the band released the Bangor Tweezer on ALO. I am not a disinterested spectator. –charlie)

CD: What in particular about Phish inspired --and continued to motivate-- you in writing this book?

WH: Love, right?

I've been obsessed with different music before: Herbie Hancock, Ornette and his descendants, tango music (and dance), electric Miles, film scores, Kid A, Andrew Bird, Achtung Baby, They Might Be Giants. I've gone through periods where I couldn't live without particular musicians -- John Coltrane especially, and a period where I listened to almost nothing but the Dead.

But I've only ever loved a small number of musicians. What I feel for Phish, beyond what I feel about their music, I can only call love.

That's half of it. But then because the center of our shared fandom, the music itself, is so particular -- the improvisatory method so finicky, the compositional voice so admirably catholic, the humour (still) so absurd, the band/audience connection so deep, the worldview so specific yet so open and welcoming -- I still find writing about Phish a compelling challenge. There's this specific thing they do that no one else has ever done in quite the same way, and even now they're exploring new areas of that art! That's so rare. I keep wanting to write something that's equal to the power of their best music.

Oh! Also the thought of making MOUNTAINS OF MONEY.

Did you learn anything new about Phish's music, or even your own musical perspectives, in writing “A Live One”?

WH: They were even better in the mid-90s than I remembered -- and I had some pretty great memories.

The project was a huge learning experience -- that's one reason I took it on. As personal as it necessarily is, there's a lot less of ME and MY story in there than there might have been.

I learned a bunch about the roots of the band, their inspirations. Only recently have I begun to appreciate how Weird (and disreputable!) some of Phish's early influences were. I'd barely heard any Beefheart before starting my research listening for the book, for instance, and didn't realize how much his painstakingly detailed private visionary weirdness anticipated Trey's and Phish's, though Trey was savvy and sociable enough to build a democratic band, which cuts against his privatizing impulses.

I learned a lot about punk and postpunk, in passing. I don't enjoy punk rock, but what I think of as the postpunk 'fusion' moment generated a ton of really interesting music. Trey's beloved Talking Heads, for one thing...

I realized that there's a (short) book to be written about the mid-80s Burlington music/arts scene and its relationship to other countercultures; I'm definitely not the person to write it, of course.

The biggest realization might be this: the music is way bigger, truer, more beautiful, than anything I have to say about it. You can see how that'd be a blow to a writer's ego, especially one with messianic pretensions. But maybe it's the start of a new, deeper understanding. I hope so.

Would you have written any sections of the book differently now that you've had time to reflect on the process after publishing?

WH: Most of it (sigh) -- but I can't trust my assessment of the book at this moment. I've been reading a lot of Greil Marcus lately, finally, and his approach to rock writing, in which every aesthetic gesture (however small) is understood as a weighty exchange in an ongoing Great American Mythic Conversation, is dangerously contagious, though wearying in large doses. It makes me want to go back to chapter 2, the long forerunners/contexts chapter that sets the stage for everything else in the book, and try to weave it together into something more continuous. Closer to the version in my head.

I'd definitely spend more time fine-tuning the chapter about 'whiteness.' (There is indeed a chapter about 'whiteness.' It's that kind of book. Why bite off only as much as you can chew, after all?) At the moment it veers a little too quickly to a defense of Phish's 'syncretism,' as opposed to 'appropriation,' and I'd wanna take more time before doing so -- think more about the roots of Phish's cultural politics. Well: I blinked.

Who are your favorite authors?

WH: John Crowley, Russell Hoban: fantasists at home with the heightened abstractions of myth-history and the most painfully intimate domestic portraiture -- and Crowley (who wrote Little, Big, an all-time great portrait of lifelong married love) works on a scale approaching that of...

...Thomas Pynchon: the best we've got, isn't he? He commands more registers, and engages with his material at more scales, than any other writer I know. Byron the Bulb? Jessica and Roger at the church? Oedipa putting on all those clothes in the hotel room? 'They fly toward grace'?! He can do everything, and is willing to try.

Douglas Hofstadter, Kenneth Hite: idiosyncratic practitioners of a kind of speculative nonfiction who demonstrate (in maximally different registers and domains) how to turn private obsessions into tools for playful creative thinking. Hofstadter is a CS/cogsci guy; Hite writes roleplaying games.

James Merrill, E.E. Cummings, Pablo Neruda: Merrill's Sandover is a 600-page visionary poem about talking to W.H. Auden and a host of angels through a ouija board. Harrowing, melancholy, regally ironic -- and incidentally a moving portrait of James and David's long marriage (in all but name). Cummings wrote maybe the funniest erotica I know -- and he was more concise than Christgau, for Christ's sake. Neruda's introduction to his 100 Sonnets is one of those perfect things; the rest of the book has seemingly limitless freedom-within-formalism that I hear in Piazzolla.

Terry Pratchett, Douglas Adams, P.G. Wodehouse: two angry sages and an elf.

Christopher Hitchens: My favourite pugilist. His dialectical arguments on behalf of the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq -- from first principles which his colleagues at (e.g.) The Nation theoretically shared -- are still unsettling, even now. A signed copy of his book Letters to a Young Contrarian, which a fan of my old blog(!!) once sent me unprompted, is one of my prize possessions. And it's a beautiful, stirring book about thinking freely and enjoying life.

David Milch: One of my heroes. He has Hitchens's encyclopedic recall, Pynchon's ear for voices, Joss Whedon's command of dialogic rhythm, and Rumi's joyful spirit -- not to mention an improvisatory spirit worthy of, lemmeseehere, Trey Anastasio himself. Deadwood's dialogue is the best ever written for TV, which wouldn't matter if its characters weren't fully realized human beings. Sidebar: his Idea of the Writer lectures are available online, and -- forgive my evangelical zeal -- they can change your life.

All men, I know, on this list at least: one of my shortcomings.

Are you (considering) writing more books about Phish?

WH: Two's enough, I think! Even my 5-year-old son makes fun of 'daddy's Phish books.' Though Phish'll make a cameo in what I think/hope is my next project, which builds on chapter 2 of the 33-1/3 book. It's not primarily about music.

If you could ask a band member any question, who and what?

WH: I'd want to talk to them all about their practice regimen, how that's changed over the years; and about their understanding of changes in the band's music in the late 90s and early 21C. And I have a lot of questions for Page about how he understands his role in the band, since he's the one whose expertise is least obvious.

Will you be at any of the MSG shows?

WH: Doubtful. A nice thought, anyhow.

Thank you for your time, Wally! For more information about the 33⅓ book series, please visit Wikipedia. And to order Wally’s A Live One, please visit Amazon.

The Mockingbird Foundation

The Mockingbird Foundation